In a world continuing to heat up, wine lovers worldwide increasingly worry what shall become of their favourite wine region.

One such region is Champagne. Champagne and other premium traditional method sparkling wines require grapes with delicate, not too intense, flavours and plenty of acid and as the world warms up, grapes inevitably will end up containing a higher sugar to acid ratio, which would change Champagne as we know it towards higher potential alcohol and less acid. A solution would seem to be to harvest earlier, but over a period of 30 years, harvest has already moved forward by 18 days or so(!) on average and in the same time span, potential alcohol has gone up by 0.7% and I need to stress, that there is a limit as to how far forward harvest can be moved.

If I asked you to name a European sparkling wine outside of Champagne, you probably wouldn’t even consider England and England is indeed still a relative newcomer in European sparkling wine production. One only needs to briefly look at the vast history of Champagne or Crémant from Alsace and Bourgogne respectively for comparison.

But in the search of new opportunities for producing world class traditional method sparkling wines, attention has turned to England and more specifically southern England.

In modern day, the first commercial vineyard in England was planted at Hambledon, Hampshire in 1952 and who would have thought, that grape growing and wine production in England actually dates all the way back to the Romans, who introduced vines to England in 43 BC. Well, it does, but fast forward to the mid-20th century.

From its beginning, modern day grape growing in England meant producing wine from hybrids and German crossings, but in recent decades (from the 1980’s and onwards) the grapes we know from Champagne are increasingly planted with the purpose of producing traditional method sparkling wine.

Today, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Meunier account for around 70% of all plantings in the country.

Since 1952, English wine and particularly English sparkling wine has come a long way, and today, according to Wines of Great Britain, more than 200 wineries produce wines from approx. 4,000 ha divided into slightly less than 950 vineyards, the majority of which are located in southern England, where East- and West Sussex combined have 29% of the area under vine with another 26% to be found in Kent.

Just how far, England has come as a wine producing country was on display earlier this year at a trade tasting at the British Embassy in Copenhagen.

15 producers came to town, all determined to show the Danes, what they’ve got!

I had no intention of going ‘all in’ in an attempt to taste every single wine on display, but had rather decided to narrow it down to tasting from producers across the different counties, some of which I knew and some of which were new to me, to get a hold of the overall picture.

Champagne remains in such huge demand and with climate change already challenging Champagne, it only seemed quite logical for some of the big Champagne houses to have started looking outside of Champagne for new wine growing areas as to hedge their bets for the future.

Southern parts of neighbouring England have similar chalky soils to those in Champagne and England is both cooler and wetter – arguably a more marginal climate for wine growing.

I have looked at different temperature data for Brighton and Epernay respectively and Brighton has roughly 20% less Growing Degree Days (GDD) than Epernay but benefits from a milder October. This extends the ripening period for English producers, who at the same time are able to preserve the vital acid levels in the grapes.

Potentially even worse hit and challenged than Champagne is Penedès and the production of Cava. 3 years of drought has hit Penedès very hard and in 2023 yields were down 45% compare to pre-drought average. This has caused Cava producer Freixenet to furlough 80% of their employees!

Hence, as the world heats up and the weather patterns become increasingly more erratic, it makes perfect sense to consider England a candidate for the next big European region for traditional method sparkling wines. And to protect their future business, foreign producers have started investing in England!

Taittinger has invested there, as has Freixenet, who purchased Bolney Wine Estate in 2022.

The English climate is still marginal and even with the current climate change, South England will not have GDD’s similar to what is considered today’s norm in Champagne for the next 80-100 years, prognoses show.

English climate results in significant vintage variation, as experienced during the 10’s with average yields in the cold and wet 2012 as low as 5(!!) hl/ha from those, who did harvest at all, compared to the abundant harvest of high-quality grapes in the much warmer and drier 2018 and even more so if compared to 2023, which is expected by Wines of Great Britain to be the new record vintage in terms of overall production (obviously influenced by the amounts of recent new plantings, too), but also in terms of yields/ha.

In a cooler and wetter climate, it is more difficult to adopt ‘hands off’ approaches to wine growing, simply due to the risk of diseases in the vineyards, but sustainable winemaking is increasingly applied. A very good example is the members of Sustainable Wines of Great Britain. SWGB is a 2020 initiative, aiming to reduce pesticides usage, minimize carbon footprints in both vineyard and winery as well as to reduce, re-use and recycle winery waste and waste water, to name just a few of their objectives.

The importance of site selection

In order to produce premium wine in a marginal climate such as England, site selection is highly important. One thing is the altitude. As a rule of thumb, you would plant your wines no higher than 125 meters above sea level. Since temperatures drop approx. 0,6 degree for each 100 meters you remove yourself from the sea level. Too cool vineyard sites would potentially result in unripe fruit rather than the just ripe and not too aromatic grapes with high acid levels required for traditional method sparkling wines.

Another potentially critical factor is the strong south-westerly winds, since e.g. Pinot Noir is susceptible to, among other things, strong winds. For this reason, you might prefer some form of shelter and hence ex-orchards are quite often chosen for planting your vines, even if this includes planting on north-facing slopes – something, you would normally avoid being this far away from the Equator in the Northern hemisphere, since you would normally tend to prefer more southerly exposed slopes to maximize the sun capture to help ripening the fruit.

How do the different producers succeed in ripening their fruit, whilst preserving the vital acid levels. How widespread is the use of malolactic fermentation? Is there any trend in terms of dosage and extended lees aging? So much to look forward to exploring at the tasting!

A safe choice in English sparkling wines and a very good reference point would be Coates & Seely in Hampshire. Their wines are always very well made and stylistically quite personal with their very limited dosage. The Blanc de Blancs showed Golden Delicious apple, lemon and lemon curd as well as merengue, all wrapped in quite a creamy texture as well as a lovely acidity.

Also in Hampshire, Exton Park produces wines from a total of 24 ha, planted back to 2003 on calcareous soil up to as high as 130 metres above sea level, which is rather high altitude for England and it only makes sense due to the vineyards’ southerly exposure.

Corinne Seely draws on reserve wines curated and stored since 2011 to produce Exton Park’s RB range, because – as they say on their website: “The secret to perfection is patience!”

RB23 is a 70/30 Pinot Noir/Meunier blend, which contains 23 different reserve wines. Direct pressing, using whole clusters, the wine displays redcurrants, raspberries, white peach and rose petal. The freshness and purity of the fruit matches very nice with the 10 grams of dosage and the wine is a lovely paring for tuna or shellfish.

Blanc de Blancs 2014 is a beautiful wine from some of the estate’s oldest vines, planted at high altitude. Extended lees aging lends added texture and complexity to this very elegant wine, that plays on green apple/lemon notes on the palate to complement the dough- and pastry aromas. I definitely understand all the high scores from critics here.

The Vineyard at Hundred Hills in Oxfordshire is a highly interesting story. Oxfordshire, not too far to the west of London, is not the first location that springs to mind in terms of producing top quality sparkling wines, but that is exactly, what they do!

Clones of Chardonnay and Pinot Noir have been meticulously selected and vineyards were divided into 10 parcels with individual soils and aspects. For instance, Pinot Noir was planted on east-facing slopes for an extended ripening season.

True to the motto, that “wine is made in the vineyard”, minimalist winemaking is practiced here and vintage variation is highly appreciated as a vital part of the “sense of place”.

Preamble No. 2 2019 is 50/50 east-facing Pinot Noir and southeast-facing Chardonnay, each enjoying the long ripening season of more than 100 days in this cool vintage. Full malolactic and 36 months on the lees. Quite a fruity expression with red and yellow apple, bruised apple and an apple cider note, ripe lime and even a whiff of pineapple. Even with the grapes being harvested late, the wine has a lovey freshness to it.

Rosé 2018 is predominantly Pinot Noir (80%) with 5% of red wine added. No malolactic here. Intense aromatics of strawberry, raspberry, berries & cream, red apple, bruised apple and gentle autolytics such as roasted nuts. I love how the acid and the intense fruit compliments each other.

Zero Dosage 2018 from 75% Pinot Noir and 25% Chardonnay is an absolutely beautiful wine in a slightly oxidative and almost Cider-like style. Fermentation in wood, 40 months on the lees and partial malolactic fermentation has brought about a high acid wine from a top-notch vintage. A wine with tons of potential.

In Kent, Gusbourne Estate produce wine from their own vineyards exclusively, the oldest of which date back to 2004. Besides 60 ha under vine in Kent, they also own an additional 90 ha in West Sussex.

Brut Reserve 2020 is made from 76% Pinot Noir, 14% Chardonnay and 10% Meunier and to make this wine 120 different base wines were used. 2020 was a warm vintage, which resulted in a very soft and smooth wine. 8 grams of residual sugar. Pomegranate, red currant and red apple, lemon and lime, peach as well as a touch of pastry.

Brut Reserve Late Disgorged 2015 consists of 63% Chardonnay and 37% Pinot Noir and the wine spent a minimum of 67 months on the lees. Kiwi-lime, lemon peel and green apple on the nose with vanilla custard, brioche and pastry, roasted nuts and sweet almonds. On the palate the fruit transforms into lemon curd, ripe apple, pear and white stone fruit. A very creamy sparkling wine, where acid and sweetness balance each other nicely.

Blanc de Blancs 2018 is a 100% Chardonnay from the warm 2018 vintage and consists of 60 different base wines. The wine spent 3½ year on the yeast and appears very ripe and fruity, a sensation the 11,6 grams of residual sugar adds to. The wine appears both full and mellow, but at the same time, the freshness is still there to provide nerve.

Rosé 2018, also from the lauded 2018 vintage. 59% Chardonnay, 23% Pinot Noir and 18% Meunier. Here we have lemon, berries and cream, red apple, forest fruit and cherry as well as autolytics such as peach melba on the palate. 10 grams of residual sugar adds to the feeling of a smooth and quite rich sparkling to drink over the next few years.

Sussex PDO

Up-and-coming wine producing countries and regions aspire for recognition and look to established, well-known and bespoke regions for inspiration and reference and what greater recognition for England than your very own PDO?

This major step for English traditional method sparkling wine towards a broader recognition was taken in July with the ratification of Sussex PDO for wine produced from grapes grown in East and West Sussex.

It is not too uncommon for English producers to produce wine from grapes sourced in different shires, but for the sparkling wines under the Sussex PDO, this is not an option.

As with any PDO, a strict set of additional rules are laid out and these include permitted grape varieties, yields, vinification and much more.

This new PDO should prove instrumental in increasing the awareness of English sparkling wines and secure consistency in terms of quality and style – that is if wineries don’t blindly rely on the PDO to cut their cake. More than one Sussex-based producer have warned against sleeping on one’s laurels, and I get the point, as it is sadly old news in the world, that sub-par wine can be – and is – made within otherwise famous PDO’s.

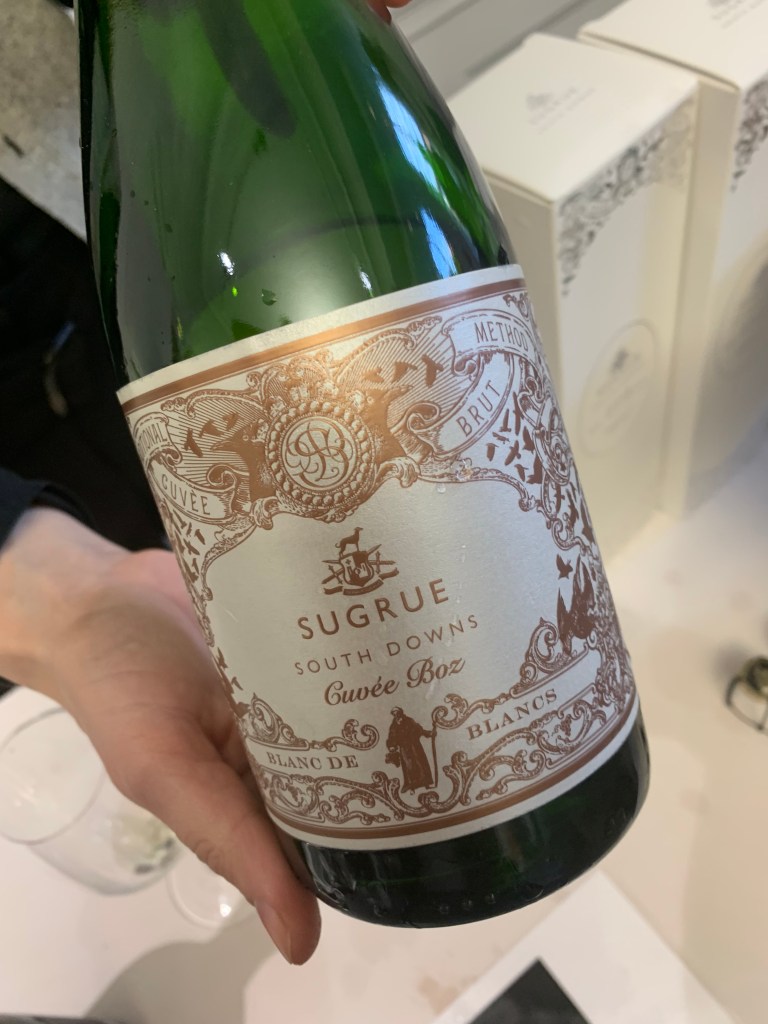

On the chalky soils of East and West Sussex, Dermot and Ana Sugrue at Sugrue South Downs work with a bit more than 12 ha. of vineyards, the oldest of which were planted back in 2005, but occasionally wine from Hampshire is included as well.

For Dermot Sugrue, it is not uncommon to use grapes from Hampshire as well, such as with his The Sugrue ‘The Trouble with Dreams’ 2017. A 60/40 Chardonnay/Pinot Noir blend from a vintage, which due to spring frosts was very limited. The wine spent 3 years on the lees and has 8 grams of dosage. A very elegant wine with a lovely balance between lemon/lemon curd, fresh green and yellow apple, salinity and autolytics (bisquit), that never take over the wine. Very good concentration that matches the fresh and crisp acidity nicely.

Rosé Ex Machina 2016. The blend is 50% Pinot Noir, 30% Chardonnay and 20% Meunier from vineyards in Hampshire, planted in 2004. Due to spring frosts, the average yield in 2016 was only 3.750 kg/ha. Some 2009 reserve wine added was added. 20% of Pinot Noir red wines is included in the wine in the same way, as can be seen in Champagne. Four years on lees and 8 grams dosage adds richness and complexity.

This is a lovely wine with aromas of red apple, strawberry, red currant and orange peel. Bisquit and pastry. Elegant with lovely finesse and a creamy expression. This is without a doubt a great gastronomic sparkling wine.

Cuvée Boz 2015 is produced from 100% Chardonnay and spent more than 5 years on the lees. Lovely aromatics with lemon merengue, lemon balm, lemon peel and fresh green apple. This is a creamy wine with substantial weight, but also with a nice freshness to it. One that displays more nutty and toasty notes such as croissant on the palate.

ZoDo is a multi-vintage sparkling wine with zero dosage. The base wine, Ana Sugrue explained, is from 2017, but it also contains wine from 2009 and 2011. 50% was fermented in old 500 litre puncheons and 50% in stainless steel. Only the latter has gone through malolactic fermentation.

The lack of dosage means, that the residual sugar is no more than 2,6 gram/litre, all deriving from the grapes themselves. This wine comes with fresh green apple, an almost cider feel, lime, oyster shell and a touch of pastry. The acidity cuts like a sword and makes the wine incredibly light on its feet.

Also based on the chalky soils of the South Down in Sussex, close to Brighton, BCORP-certified Rathfinny Estate is arguably one of the English wineries located the closest to the sea. Their first vines were planted in April 2012 and today they have 93 hectares under vine, all in one single-site, predominantly south-facing vineyard just 3 miles away from the English Channel.

Classic Cuvée 2019 is 44% Pinot Noir, 41% Chardonnay and 15% Meunier and displays aromas of lemon and lime, ripe, red apple and autolytic pastry-notes as well as a lovely mineral sensation. Crisp acidity.

Rosé Brut 2019 consists of 60% Pinot Noir, 22% Chardonnay and 18% Meunier. Ripe red berries, red apple and a peach melba. The dosage remains modest at 5 grams and the wine possesses a lovely freshness. To me, this is a sparkling that suggests itself to accompanying a lovely meal rather than being served as an aperitif.

Blanc de Blanc 2019 is 100% Chardonnay with aromas of ripe apple and lemon as well ripe stone fruit and subtle autolytics. The full malolactic and the low level of dosage at 3 grams matches the creamy texture and the fresh, lively acid beautifully.

Blanc de Noirs 2019 is a beautiful wine made from 81% Pinot Noir and 19% Meunier. Red apple, red currant, red cherry and blackcurrant leaf and the low dosage (3,5 grams) makes this wine so appealing.

What will the future hold for English sparkling wine?

Well, we obviously don’t quite know.

Based on the quality of what was put on display in Copenhagen as well as the foreign interest in investing in England’s wine country, the future looks bright.

Lots of high-quality wines and still plenty of room to grow, learning alongside each other and from each other as well as from other regions, established as well as fellow up-and-coming ones.

According to ‘Wine GB 2023 Harvest Report’ from Wines of Great Britain, the number of hectares in production in English and Welsh vineyards almost doubled from 2012-2020 and from 2012-2023 hectares even increased from 1,297 to some 3400 ha.

And compare the 13.11 mil. bottles produced in the record year of 2018 to the 20-22 mil. bottles, which are expected to be put on the market from the 2023 vintage. Quite a dramatic increase in production.

Swinging London, next-door neighbour to the wine country, will obviously continue to generate a certain demand from a big concentration of people capable of and most likely willing to pay the super-premium prices, that many of these sparkling wines command. Similarly, London was always a very important market for fine wines and a magnet to wine lovers and trade people from across the globe. Exposing all of these wine loving professionals, tourists etc. to first-hand experiences in the wine country seems highly important.

Champagne is not going away and many a very good Champagne is available at the RSP of most English bubbles, and the majority of end consumers still buy into the ‘safe haven’ idea. Hence, getting the price points right is vital – especially with a projected continued increase in annual output.

It is obvious, that the English producers are preparing to expand on the export scene, but the battle, though, has to be won domestically and the big question remains, if London and England can continue to provide the domestic demand necessary to meet a seemingly ever-increasing supply.

The first important step, is to get people to order a glass of English sparkling wine at the wine bar – and maybe, just maybe they might start out with ‘a glass of Sussex’.